SINNER, PUBLIC ENEMY NO. 1

- Oct 26, 2025

- 3 min read

Ghosts and shadows of a stateless tennis player.

The Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera ran a headline this week: “Vespa, another attack on Sinner.”

Summary: After calling him “too German” and criticizing his residence in Monaco, veteran TV host Bruno Vespa is once again going after Jannik Sinner.

After surviving Alcaraz’s drop shots and Djokovic’s backhands, Sinner has found a new opponent: Bruno Vespa.

The question writes itself: why is Italy’s most established political journalist — usually allergic to taking sides — lashing out so fiercely at a young man whose job is to hit tennis balls?

The thesis is simple: Sinner is a political problem.

The model citizen of the post-nation

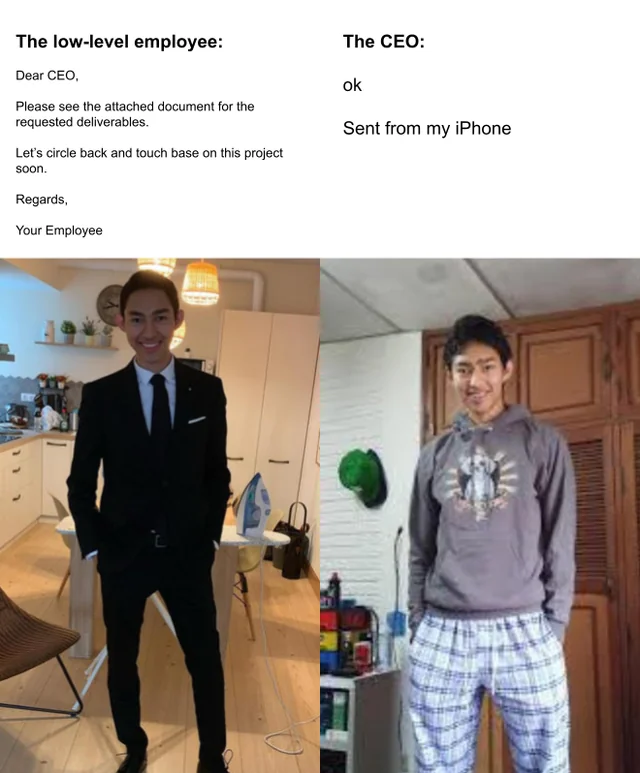

Sinner embodies a new social class: successful young professionals — mostly under 40 — who have made performance their way of life.

Determined. Precise. Robotic. Lean, powerful, hyper-focused. Inhuman.

His only objective: to win.

He is the quintessential product of our age — the age of top performers. People who measure their worth exclusively by their results. Everything else can go to hell.

In such a mindset there is no space for patriotism, civic duty, or collective ideals — only for maximizing income and minimizing costs.

Sinner lives in Monte Carlo (to minimize taxes), skips lunch with the President of the Republic (to optimize his schedule between tournaments), and refuses to play Davis Cup for Italy (to “maximize physical and mental recovery”).

Anything that doesn’t serve performance — and by “performance” we mean ranking and earnings, which are the same thing — is discarded.

But Sinner isn’t just a hyper-focused machine: Sinner wins.

And that’s what drives the system crazy.

His success earns him front pages, sponsorships, luxury cars, glamorous girlfriends — all without ever passing through the traditional Italian power circuits.

In fact, in spite of them.

From the perspective of Italy’s political establishment, Sinner is an alien: he shows up, eats for free, and doesn’t pay the bill.

He has proven that it is possible to live outside the State.

Sinner is a stateless citizen of capitalism 3.0.

The new class with no homeland

In a global economy of circulating data and capital, his income comes from Wimbledon to Dubai, his sponsors are multinational, his audience universal.

What emotional tie could he possibly have to the country where he just happened to be born?

And he’s not alone.

We work for Dutch-registered corporations with Chinese suppliers, American servers, and clients from Abu Dhabi to Tokyo.

We unlock a phone — Made in China. Designed in California. — and inhabit apps that float above geography.

For Sinner’s generation, the State is not a moral community.

It’s an administrative nuisance.

A bureaucratic relic.

A tax institution, not a sense of belonging.

That’s where the political problem begins.

Imagine a generation like his: people who don’t vote, don’t pay taxes, don’t feel national pride — and don’t show up when the President calls.

A few months ago, Italy’s Chief of Defense Staff, General Masiello, said: “Today, only one in five Italians would be willing to fight for their country.”

It’s the end of the nation’s founding premise: that the common good still matters to everyone.

Sinner says, essentially: It doesn’t matter to me.

“I made myself. My talent pays for my needs. I owe nothing to anyone.”

The message is surgical: if you succeed, you can afford to ignore the State.

The crisis of control

Vespa — and with him, the political class — faces a new kind of monster:

uselessness.

Loss of control.

Delegitimization.

No one had ever snubbed the President of the Republic like this.

But the truth is, today’s winners all look like Sinner.

Take another example: Tadej Pogačar, the Slovenian cycling champion — also fiscally domiciled in Monaco.

“When I finish,” he said when accused of wanting to win too much, “I’ll probably not speak to 99% of the peloton. I’ll focus on my close friends and family. I don’t care too much about what everybody else thinks.”

Translation: me first, then my inner circle, then — maybe — everyone else.

The horizon is global, the identity private, the clan the only community that matters.

Success absolves all sins.

It’s the moral code of late capitalism: if you win, you’re right.

Sinner, the winner, becomes a role model.

And if two generations grow up thinking like him, the State might as well surrender.

Winners no longer need it.

They make money in London, spend it in Dubai, get treated in New York.

Nationalism is the opium of the losers.

The tricolore is the flag of the left-behind.

For Vespa — who built his career and his identity through the State and its institutions — Sinner is terrifying.

Truly terrifying.

Today, Jannik Sinner isn’t just an athlete.

He’s a political problem.

Comments